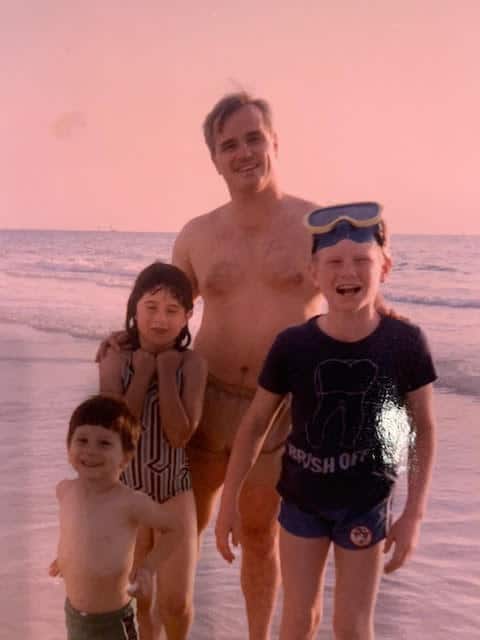

The hot Clearwater, Florida sun demanded that we turn up the AC in the rental car on our way to the funeral home. As Christy and I drove up to the faded yellowish-white brick building, I felt the familiar tension of grief deep in my body. I knew this feeling, though this loss was fresh. Grief has a familiarity to it; lost loves, my son, and my sister-in-law had all prepared me to face my dad’s lifeless body. My siblings did not feel the need to see his body, but I strongly needed to as a way to say goodbye and to make sense of all this.

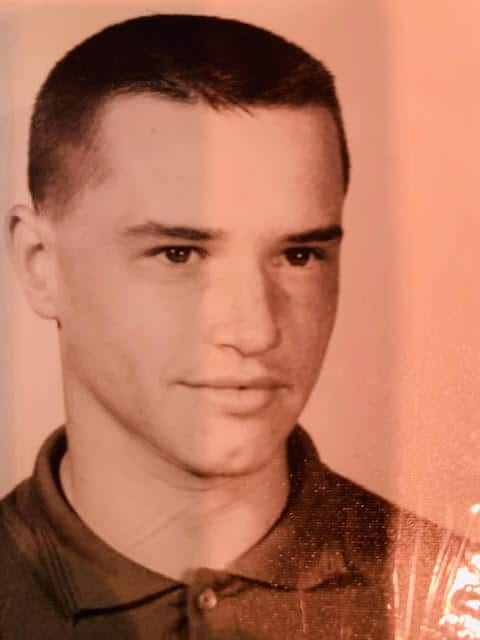

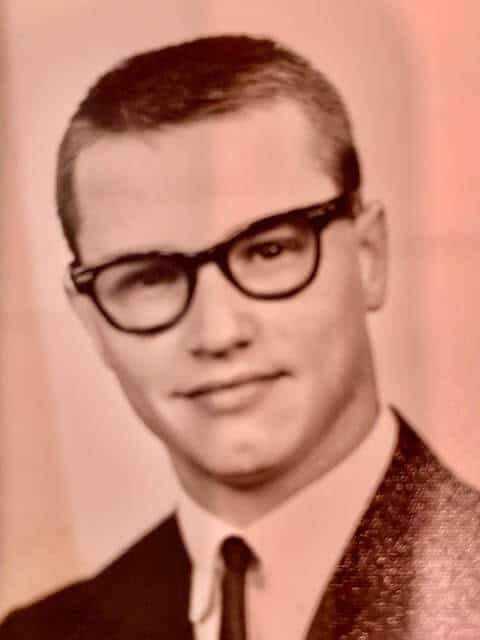

It had happened so suddenly. He was recovering from gallbladder surgery on Monday, talking to the nurse about his kids and doing well. Not long after that, he told the nurse he was not feeling well and his blood pressure suddenly dropped, his eyes rolled back in his head, and his heart stopped beating. They tried for 45 minutes to revive him. He was ready to go, but I still had things to tell him. Maybe that’s why I needed to face his body, to tell him the things he wasn’t ready to hear while he was alive.

The funeral director greeted Christy and me boisterously at the door. The brash loudness of his voice on such a somber occasion caught us off-guard. As we walked into the dimly lit entryway, we were surrounded by musty 1970s decor. Without ceremony, he hastily grabbed the viewing room door handle and invited us to walk into the room where my father’s body lay. I stopped him and asked for a moment to prepare my own body, and for some water to help soothe the lump in my throat. A staff woman hastily passed by us into my dad’s viewing room muttering, “Oh hell”, then turned to us in apologetic horror upon realizing that we were standing right behind her.

The chatty funeral director quickly changed the subject, asking where we were from. “Seattle”, Christy answered. She attempted to buffer his insensitivities as I stared silently at the door, trying to swallow my dread. He began showing us pictures on his phone of his daughter’s apartment; she had apparently just moved to Seattle. I felt the urge to punch his mouth to make it stop moving, but decided it would be more productive to face my father and my grief that was so close to the surface. I interrupted his monologue about Seattle traffic and told him I was ready to see my dad.

He opened the door to reveal a large viewing room where there were over thirty chairs set up and facing my dad’s body. We slowly began to walk to the front of the room, but I had to stop about 5 feet away. I could not move any closer. My tears and loud moans began as I tried to wrestle with my body to move nearer. After about a minute or so, I had to turn my back; it was all too much to bear. I stood there and wept.

While he was alive, he had asked to be cremated, so there was no casket. My dad was lying on a bed covered by a blue patchwork quilt. He looked so peaceful, I could have mistaken him for sleeping. I kept wondering if he was going to open his eyes if he would wake up if maybe I would get another chance to talk with him. It felt strange and wrong that no one else was there to witness this.

I wept for a long time, surprised by the amount of unlived life I was grieving; all my hopes and years of fighting for my father to be someone he could not. He was like a familiar stranger. After my tears subsided, I asked Christy to sing. Soft stanzas of old hymns gently filled the room. Then I played a song my father loved, Daddy’s Song by Dennis Jernigan. Another wave of emotion swept over me and I asked Christy to leave so I could be alone with him.

“Why, Dad, why? Why were you not around? Why??” I continued to ask, hoping to somehow understand how he had remained so distant and uninvolved in my life. I thought about what a cool person I’d turned out to be and how much he had missed out on. I told him I forgave and loved him. I told him the truth; that I was disappointed and had needed him when he wasn’t there. I wept loudly.

I could hear my old nemesis, the funeral director, talking to Christy loudly outside the door. I asked her to come back in, hoping that would leave no one for him to squawk at. I felt ready to leave, yet I didn’t want to. I felt guilty for leaving his body alone. I didn’t want to turn my back on him when I walked out, so I asked Christy if we could walk backwards to the door. Finally, I said: “I love you, Dad. Goodbye”, and closed the door.

Knowing my dad was now in these folk’s hands, I wanted to ask the funeral director to be gentle with his body. I waited in the lobby for a while but I was so raw, I could not handle his inevitable blundering, so I asked Christy if she could give him the message for me. She agreed, and I went to the car and tried to catch my breath as I allowed the tears to continue to comfort my weary, tender heart.

“I love you, Dad. Goodbye.”