This past week Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh has been accused of sexual assault, resulting in a political firestorm of controversy and contention between abuse advocates who want women’s stories to matter, and senators looking to safeguard their political agenda by securing a conservative Supreme Court justice. The President even weighed in on the validity of Dr. Ford’s attempted rape claim. His tweet prompted the #WhyIDidntReport hashtag, which has produced thousands of sobering disclosures from victims of sexual assault, giving insight into why they chose not to report the abuse. Many expressed a debilitating fear of judgment or backlash. Unreported sexual abuse is an enormous blight on our society. Dr. Ford’s heroic testimony on Thursday creates for us a learning opportunity that must not be missed, as we attempt to navigate these multifaceted times.

Our cultural norms must change to create an environment that supports women’s experiences; and a victim of sexual abuse must not be bullied by questioning her or his handling of the traumatic event. (Ford, for example, was just 15 years old.) Considering the courage, it takes for the abused to face their stories of deepest shame, why would we question and casually dismiss them (like the President did) by questioning how bad the experience actually was? Why would we re-traumatize someone so flippantly? Sure, all the facts are not yet fully known, which is the very reason why we should not be indifferent about something so deeply painful and violent. It’s important to note that research studies have been conducted in the US and in Europe determining that only 2 to 6 percent of sexual abuse allegations are false. I understand this topic from many sides: as a mental health therapist who works with sexual abuse survivors, as a sexual abuse survivor myself, and as a recovering misogynist and abusive man.

A number of clients in my private practice explain how they are scoffed at, dismissed, or even ignored by authorities when reporting sexual harm. Authorities who are not trained to respond in an educated manner may embarrass the victim as s/he attempts the courageous act of speaking out about his/her experience. While the simple act of reporting is costly and often triggers additional pain for the victim, a loss of self-efficacy is inevitable when the report is denied or diminished.

In an effort to help my clients process and heal from their pain, I help them delve into the years of shame around their bodies being violated. Many victims personally know and care for their perpetrators, creating an environment where they would not have been believed at all, or their trauma would have been minimized or dismissed. “It’s just boys being boys.” “I’m sure he didn’t mean to touch you.” “Well, what were you wearing? You have to be aware not to bring on his advances.” These and similar sentiments have been expressed to many victims in an attempt to silence their voices and prevent them from rocking the boat or disrupting the family system. These comments unconsciously encourage victims to internalize their harm and communicate that their bodies are worth less than the systems (families, churches, or organizations) many aim to protect.

So these men and women try to forget; they become addicted or learn to hate their own bodies; they tell no one as means of survival. Their families are often unwilling to talk about uncomfortable topics and their religious communities choose to ignore it completely. Or the HR department says they will handle it, but there are no discernible consequences. And these wise and courageous victims learn how to live with less hope and more caution.

I also know this topic from a victim’s standpoint, though not from a woman’s. This adds another layer of complexity to my perspective: because of my male privilege, I’m more likely to be believed than a woman.

After experiencing childhood sexual abuse, I felt paralyzing shame, overwhelming fear, and a complex array of seemingly contradictory emotions that were way too difficult and intense for me to articulate. The abuse came from my best friend’s older brother. He touched my penis while we were all wrestling. I felt so uncomfortable, I immediately backed away and asked him why he did that. He responded that he wanted to see what it felt like. That was the end of the conversation, and I did not know what to do next. Frozen, I thought about telling my parents, but knew nothing good would come of that. I talked to my best friend, and he confided that his brother had touched him before too. I did not want to get anyone in trouble; I also wanted to keep playing with my best friend. I weighed the options and, in my 12-year-old mind, not saying anything felt like the best decision. Looking back, of course, I wish I had spoken up, but I am kind enough to myself now to know it wouldn’t have made a difference.

I am also aware of another scene of abuse regarding an older man I trusted, a memory that I had blocked out altogether. It took me nearly 25 years to recall, and I was well into my career as a sexual trauma therapist when it resurfaced for me. Suddenly the deep violation, the searing betrayal, and a torrent of questions about my experience all came flooding back into my mind. I eventually summoned the courage to tell that story, but still it hurts. My chest tightens, and my throat becomes lumpy, and tears fill my eyes.

I am wondering, Mr. President, if I, too, am to blame for my lack of reporting?

I know this topic not only as a mental health professional and a sexual abuse victim, but also as a recovering abusive man. When I say I was an abusive man, I don’t mean physical violence. I didn’t fit the typical stereotype of an abuser; many men don’t. At its core, abuse stems from a desire for control. My grasping for control looked like manipulation, using my positions of power to get what I wanted, and objectification of women as means to excuse my abusive behavior. Deep down, I believed women were less-than. No one would have said that out loud, but growing up in my white evangelical utopia deep in the South, we all knew it was true: men ruled the world. My presidents: always men; my pastors: always men. Most CEOs, elected officials, and anyone I knew who had real power, authority, or influence was, like me, a man. I wanted power too. Of course, I genuinely wanted to make a difference in the world, and I genuinely believed that developing a domineering masculinity was the best way to accomplish this. I was your typical nice evangelical sexist. My abuse was more often covert, shrouded in Christian cultural and social norms.

To begin to break down the societal norms of sexism and change this all-too-common story line, we must address the root issue: men. Dr. Jackson Katz, an internationally known educator on violence prevention among men, has led the way by naming violence against women a men’s issue, since 99 percent of rapes are perpetrated by men. Katz states, “It’s about the guy and his need to assert his power. And it’s not just individual men, it’s a cultural problem. Our culture is producing violent men, and violence against women has become institutionalized. We need to take a step back and examine the institutionalized policies drafted by men that perpetuate the problem.”

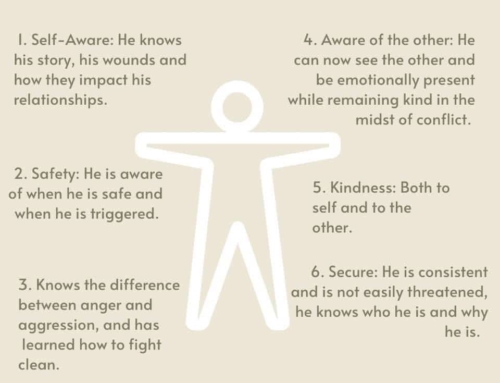

Men, we must begin to take responsibility for our role in creating and perpetuating this toxic #MeToo culture. We must look carefully into the mirror at our own desire for power and control, and how we selfishly use women to get those needs met. We cannot transform what we do not first own within ourselves. Father Richard Rohr calls this part of us the “shadow self.” He writes, “The shadow is that part of the self that we don’t want to see, that we’re always afraid of and don’t want others to see either.” Rohr goes onto say, “The shadow self is not of itself evil; it just allows you to do evil without calling it evil” (Things Hidden: Scripture as Spirituality, pp. 76–77). This is an important distinction; the core of most men is good, yet they are ensnared in the trap of denying their shadow self. The result is men who are simultaneously sexist and unaware of how they contribute to the problem.

It’s a painful and humbling experience to name our “shadow,” yet we must in order for this cycle to end. We are the ones in power; we are the ones who continue to use our privilege to advance ourselves and those like us; we must be the ones who make it stop.

It’s important to note that admitting our failures and facing our “shadow” does not mean we are bad men. It means we can make space to change and begin to allow forgiveness into our lives. Instead of avoiding these stories of failure completely or denying their existence, we can begin owning up to and taking responsibility for them. We can get help for how we are treating our spouse, or with our issues with rage, or with objectification of women. We can make the proper changes to ourselves, so we can be advocates rather than abusers. By acknowledging our role in perpetrating this system of violence against women, we can begin to change it.

I believe we can do better. Let’s replace #MeToo and #WhyIDidntReport with a culture of honor, truth, and safety. Educate yourself on this issue and be a man who stands up to misogyny and violence against women, rather than someone who perpetuates it.